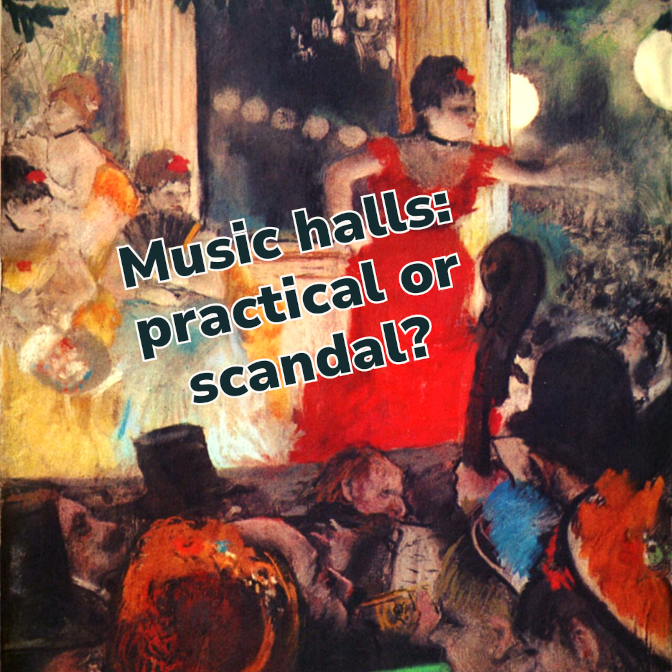

Over the course of researching historical women flutists, I’ve come across several mentions of women who performed in Victorian music halls. Just like in modern times, even though industry narratives center “traditional” concerts, in reality many performers also play other gigs – including pit orchestras for theatres and entertainment for weddings, parties, and/or local bars.

However, the music history courses I remember from college mainly talked about large, staged public performances, with only a passing reference to music salons in discussions about Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn. But as salon gatherings tended to favor pianists, vocalists, and composers, women flutists are often excluded by those narratives.

So how did women who played wind instruments professionally fit into the musical tapestry of 19th century Europe? What were music halls all about, and why did women virtuosos seem to gravitate towards those gigs? And, perhaps more importantly, why don’t we learn about these types of musical spaces in school?

Read on for a brief introduction to music halls from the 19th century!

Victorian Music Halls

Music halls began in London in the 1830s as an evolution of public house entertainment. In the 1860s, they migrated to Paris when French restrictions on costumes and programming began to loosen. Their popularity corresponds almost exactly with the time period of Romantic era music (1830-1900).

19th century music halls programmed a wide range of performers and entertainment styles which included comedians, musicians, dancers, jugglers, impersonators, aerial acts, magicians, puppeteers, and drag artists.

Their audiences were typically working-class men (initially, women were not allowed admittance). Attendees purchased tickets for admission to a show, and sat at tables on the auditorium floor where they would be served drinks, appetizers, and sometimes dinner. Unlike traditional theatre or opera, the cheap seats were in the balconies, as those patrons had to return to the main floor for their refreshments.

Throughout the 19th century, this style of entertainment was known as “music hall,” though “variety theatre” started to evolve out of these venues in the 1880s. In its 20th century form, these programs became known as “variety shows” (or “vaudeville” in the US).

Music hall venues were initially a response to urbanization during the Industrial Revolution – mass migration to cities, parks like Vauxhall Gardens giving way to development projects, and an increase in class mobility created an increased demand for new entertainment. However, they died out after the World Wars as people gravitated towards swing bands, jazz, and the new invention of the cinema.

Practical Considerations

19th century women had a really hard time trying to gain entry into “traditional,” male-dominated performance spaces due to a combination of strongly gendered social conventions and stereotypes popularly believed at the time. However, this wasn’t a type of venue designed by or for women (unlike music salons) – so why did we find so many women here??

From a practical perspective, the logic is this: if they were excluded from “traditional” concert halls, and were gonna be treated like a novelty anyways, they might as well make good money out of it.

This reasoning even held up from a masculine point of view, as seen in Hans Mirius’ article “Original Female Artists” in Die Woche, a Berlin newspaper. He seemed to consider the decision a no-brainer:

“The few [women] flautists who have hitherto appeared in public, equipped with significant skills, have by no means lacked in artistic and external successes; one liked to hear her on the concert stage, and if one or the other later turned to the specialty stage, it was because the flautist is still regarded as a specialty and because more money can be earned in the variety shows.”

Hans Mirius, 1907

“Lowbrow” Venues, “Highbrow” Repertoire

However, despite those practicalities, many critics were quick to dismiss these musicians and their performances. They tended to treat these women as show girls, focusing on their appearance instead of acknowledging their musical and performance skills (this is also related to the social construct of “respectability,” which I’ll get into in a bit).

In order to counteract the stigmas of playing in a lower-class performance space, many of these women continued to program repertoire from the classical canon. This was not only an attempt to highlight the fact that they were as technically skilled as their male counterparts, but also an effort to collect on the social capital associated with works by famous composers.

The reviews of their performances also reinforce these choices, as many critics qualified any positive feedback with a note saying that the performer insisted on selecting “highbrow” music, despite their choice of venue. Two women flutists who exemplify this strategy are Cora Cardigan and Panita.

Cora Cardigan

Cora Cardigan (stage name for Hannah Rosetta Dinah Moulton) was a British virtuoso who played piccolo, flute, and violin, and had an extremely active career from 1879-1908. She played in theatres and music halls across the United Kingdom, including the Royal Aquarium, Oxford, Covent Garden, and the Royal Music Hall. Her performances were a highlight of the show when she toured with Lila Clay and her Musical and Dramatic Company of Ladies, and her repertoire included works by Weber and Kuhlau.

Panita

Panita (stage name for Erika von Klösterlein) was a German virtuoso flutist who performed in variety shows around the turn of the 20th century. She toured internationally more extensively than Cora Cardigan, with stops including Prague, Vienna, Salt Lake City, and Portland. Her repertoire included works by Mozart, Toulou, and a transcription of the Carmen Fantasy by Wilhelm Popp.

“Put a red mark opposite the name of Mme. Panita – Flute player extraordinary. She has courageously kept up the musical standard of her act, and apparently if vaudeville audiences don’t like the difficult and rather classical selections she plays, that is their shortcoming, not hers.”

The Duluth News Tribune, 28 August 1911

Victorian Social Reform

Despite the associations of complex classical repertoire with virtuosic skill and personal reputation, this preference also (whether consciously or subconsciously) reflected classicist perspectives of the day. In response to Victorian era trends in social reform, late 19th century music hall managers started a movement to clean up their acts in a bid to attract audiences from the growing middle class.

“[Cora Cardigan’s] performances, a music hall manager said, were appreciated by him because they helped to raise the music halls above the level of clever comic singers and acrobats.”

The Musical Herald, 1889

Programming choices for their shows were an important part of that, and for better or worse, this opened up opportunities for women who performed classical repertoire – including longer works and the “absolute” music typically seen in bourgeois musical institutions around mid-century.

Performing Respectability

Despite the successes that some women experienced with music hall performances, this alternative venue wasn’t a perfect solution. The “bawdy” associations of these shows actually fed into some of the more dominant stereotypes about women instrumentalists, and steady employment did not shield them from the ever-present cloud of Victorian “respectability.”

What is “Respectability”?

Victorian society was big on the idea of “separate spheres” for women and men – women provided domestic duties, raised children, and were the moral center of their families, while men were professionals who worked outside the home. As a result, music-making deemed appropriate for women featured gender-affirming instruments (such as piano or harp) performed in private spaces (like a salon or drawing room). Anyone who stepped outside of those norms was deemed “indecent” or “vulgar” – no matter their skill at their instrument of choice.

Abiding by terms of “respectability” was easier said than done, as the concept eludes a specific definition by design. It’s a social construct from the Victorian era (1837-1901) that was used as a normalizing force for social organization. On the surface, the upper classes associated “respectability” with etiquette. However, following the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), these rules became an increasingly complex unspoken social code that marked the boundary between those with “old” and “new” wealth.

Under conventions of “respectability,” the more rules you effectively abided, the better your public reputation (and therefore your status). Some additional customs included no excess of indulgences, devoting your leisure time to personal betterment, and, last but most importantly, respecting the existing social structures – which cemented a self-perpetuating cycle that we still see echoes of today.

Greek Revival

Unfortunately, this era’s revival of interest in Greek classics only made matters worse for women flutists. Among the stories told to warn women off of flute-playing included a tale of Athena, who threw away her favorite instrument after seeing a reflection in the river of the way her face looked while playing it, and the myth of Pan, a god of nature who used flute music to seduce women.

As if that wasn’t enough, flute playing was also associated with hetaira, like Lamia of Athens. Hetaira were highly educated courtesans in ancient Greece. Through a Western lens, they were often seen as prostitutes. However, in addition to companionship, they performed artistic and intellectual services for their clients – and in reality, were more often renowned for the latter.

Some modern scholars believe that a sexualized image of women soloists helped to compensate for the threat of non-gender-conforming women. But that’s exactly the problem – these myths were weaponized to enforce the social mechanisms that restricted women to the private sphere, with dire consequences to the social reputations (that could have very real effects on the personal safety) of anyone who dared to deviate from the norm.

French Patriotism

Why was it so incredibly important for women to stay home and manage a household? We can see a clue in the stigmas against “hommesses” in post-Revolutionary France. Essentially, the hard work of getting society back on track following the French Revolution was placed on women, with a lot of emotional labor provided under the guise of being the “moral center” of their families. People were afraid of social collapse, and so fulfilling these roles also became considered women’s “patriotic duty.” As a result, deviating from these expectations resulted in a high degree of social stigma.

A Few More Thoughts…

I’ve spent the vast majority of this post talking about the socio-historical (and political) context around women’s music hall performances rather than the shows themselves – so why is that more important?? In a modern world where we still see under-representation of women composers and performers in Western classical music, it’s vital to understand how this exclusion came about in the first place.

Not having a well-rounded view of historical music-making can also limit our imagination for what musical careers of the future can look like. And as modern musicians, our jobs often include a much wider array of gigs than the recital and orchestral performances that dominated our academic lives. These are much more aligned with the experiences of our historical counterparts than you might think.

There’s a historical inclination for performers to be judged by the people that they play with, their accolades, and the reputation of the ensembles they play in. However, just like in the present day, taking gigs with less formal productions or playing “pop” music doesn’t invalidate your skills or your ability to express yourself through music.

Likewise, the lower-class and less “respectable” connotations (by outdated Victorian standards) of music hall performances should not exclude them from our music history discourse – especially when they played an important role for women who persisted in their careers despite the music industry’s glass ceiling. Just because we don’t learn about traditions of women musicians in university education doesn’t mean that they never existed – and this is just one small piece of that puzzle.

To continue learning about women in flute history, check out the additional resources below!

Additional Resources

Music Hall Flute Repertoire

A playlist inspired by surviving records of 19th century music hall performances featuring female virtuoso flutists, and flute compositions created by their teachers.

Historical Women Flutists – from Astley to Taillart

Just because women instrumentalists aren’t commonly discussed in music history classes doesn’t mean they never existed. Read this post to meet 24 trailblazing women flutists, from ancient Greece to 20th century America!

Virtuosa Flute Solos Database

To continue exploring the world of flute music by women composers, check out my database of over 160 flute solos by women composers! This list includes music from both historical and modern times, so whether you’re looking for an alternative to C.P.E. Bach’s sonatas or are curious about extended technique, I’ve got you covered. Click the link above to check it out!

The Women’s Orchestra Movement in 20th Century America

How did women instrumentalists make the leap from being restricted to performing outside the concert hall to becoming accepted inside it? Read this blog post to learn about women’s music activism at the turn of the 20th century!