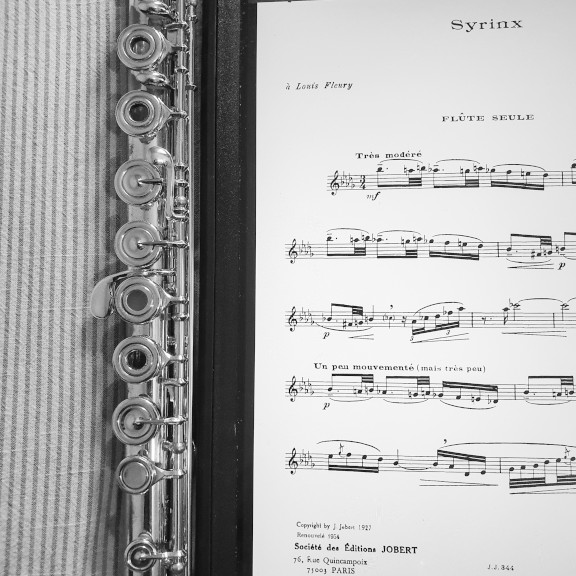

A while back on my Instagram stories, I posted a video about reframing anti-feminist works and why I’ve never played Debussy’s Syrinx. At the time, I couldn’t figure out how to upload a video of longer than one minute to my main feed – but after I did figure it out, I realized this discussion would be better as a blog post where I could more thoroughly explain my thoughts.

There are so many facets to supporting women in music – it’s not just about the stuff we’re adding to musical education. Sometimes, it also involves taking a hard, honest look at some of the things that are already there – that we may have taken for granted and/or enjoyed in the past, and might have complex feelings about moving forward.

In my opinion, compositions featuring stories of Pan are some of the most problematic in the classical flute repertoire – and I hate to say it, because some of these works truly are beautiful pieces of music. However, I just can’t get past the underlying tales they’re based on and the glorified behavior of Pan as an individual. Read on, and I’ll tell you why.

Trigger warning: this post discusses content with sexual themes. The Greek myths in the next two sections have plots that include sexual harassment and sexual violence. After that, I mention two operas with scenes that include sexist treatment of women and the validation of rape.

To skip to my suggestions on alternate repertoire, check out my post on pastoral flute music.

Who is Pan??

Godly Origins

Pan is a Greek god of nature associated with shepherds, goatherds, and their flocks; spring; and fertility (and therefore, also with sex). His center of worship is Arcadia, a rural area of Ancient Greece. Scholars aren’t totally sure about his parentage, but there’s some consensus around Pan being the son of Hermes and Penelope, born during Odysseus’ absence.

Pan appears as a faun with the upper half of a human man (with the addition of goat horns on his head) and the lower half of a goat – and he’s not considered attractive in any stretch of the imagination. In fact, most characters in his stories find Pan’s appearance alarming. Authors often characterize Pan with wild, out-of-control behaviors, unbridled creative energy, and being lustful, sportive, entertaining, vigorous, and short-tempered.

There’s some interesting contrasts in the linguistic origin of his name: some stories say he was called Pan because it means “all” in Greek and all the other gods loved him (there’s a joviality associated with Pan’s behavior in these retellings). In a second interpretation, the origin of Pan’s name comes from the Arcadian word for “pasture.” However, other stories say his name forms the root of the word “panic” – his wild behavior is considered unpredictable and dangerous, causing people to become terrified and act like a stampede of frightened animals.

Panic and Problems

Pan is often depicted hanging out in summer pastures, playing music, and frolicking with nymphs (minor deities who are all female and personify elements of nature). However, he’s also a womanizer, and the nymphs in his stories never reciprocate his affections. Pan never takes that rejection well, and several nymphs who find themselves caught in his attentions meet dire consequences for denying him – including Echo, who is trampled by stampeding animals, and Pitys and Syrinx, who become transformed into plants (more on that in a minute).

Inspired by those nymphs’ misfortunes, tales of Pan’s exploits & his use of flute music to seduce women were used during Victorian times as cautionary tales to discourage women from playing the flute. That sexualized association also contributed to stereotypes that characterized women flutists as scandalous and improper. However, punishing women with increased social restrictions seems backwards in this situation – those nymphs were victims, not perpetrators, in Pan’s stories.

The Myth of Pan & Syrinx

There are several tales that feature the exploits of Pan or include cameos of his character, but in the flute canon, a majority of pieces center around the myth of Pan and Syrinx. Here’s what happened: Syrinx, a wood nymph, was on her way to meet Diana, the goddess of the hunt. They were supposed to go hunting together; however, on her way to their meeting place, Syrinx came across Pan in the woods. He had developed a deep obsession with her, and started stalking her – causing a huge problem for Syrinx, who wanted absolutely nothing to do with him. In an attempt to get away, she ran off through the woods – but Pan followed in hot pursuit. When Syrinx came across the river Ladon, she begged the nymphs of the river for help.

Caught totally off-guard, the other nymphs did the first thing they could think of – and transformed her into some reeds growing by the water in an attempt to hide her. Pan burst out onto the riverbank, intending to seize Syrinx – but she was nowhere to be seen. But she wasn’t safe yet – a breeze blew through the Syrinx-reeds, and Pan was struck by how beautiful they sounded. So he cut them down and made them into a panpipe.

This is the part of the story that really gets me: Syrinx was going hunting at the beginning. She’s not weak, and doesn’t seem to me like someone who would just give up and accept her fate. But in many retellings, that’s exactly the implication – she ends up trapped forever (literally, since Pan is a god) at Pan’s side, and he can use her whenever he wants, subject to his whims.

Most retellings I’ve seen gloss over this part, and I’ve yet to find a version of this myth that considers Syrinx’s point of view – but if that was me, I would have been scared as hell and screaming bloody murder.

I personally don’t know how to tell a story like this with a healthy mindset, from my perspective as a modern woman. So I’m not comfortable playing pieces based on stories of Pan (even though in terms of aesthetics, Debussy is one of my favorite composers). I’d also never recommend these works to a student, even though there are a good handful that have been long accepted and normalized as part of the traditional flute canon.

Reframing Anti-Feminist Works

Not Only for Opera

We mostly see discourse around anti-feminist works surrounding opera productions, as it’s much easier to see when there’s a clear plot that’s explained through acting, dialogue, and lyrics. For example, there are scenes in Don Giovanni and The Magic Flute that suggest the validation of rape (these aren’t necessarily the most representative of operatic works, but I’m picking on Mozart here because as a flutist, my knowledge of opera is limited and analyses of these works are more accessible). But it’s important to realize that instrumental music tells stories too, and those narratives can look very different from a woman’s point of view.

Recent studies in the UK have found that girls make up almost 90% of flute students ages 6-19, and women hold about 60% of orchestral flute chairs in major orchestras (Hallam, 2008; Scharff, 2015). So even though Western societies have patriarchal norms and a male-dominated music industry overall, for flutists in particular, it’s super important to be mindful that the values and ideas expressed in our music might be perceived differently among members of our community.

The Context of Time and Place

Compositions from historical eras were created in very different times, with less general awareness of social and ethical issues than many of us have been exposed to as a result of movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter. However, it’s important to be mindful of how the values expressed in these pieces interact with our values as modern teachers and performers. These socio-cultural meanings can and do change over time – that evolution is natural and totally ok, but it’s something we do need to reconsider from time to time.

Stories of Pan became popularized during the 19th century, when there was both a revival of interest in Greek classics and a popularization of art that romanticized nature and country life (in response to rapid urbanization during the Industrial Revolution). Pan, as a flute-playing nature god, embodied the intersection of the two – which is a big reason that flute music about him became so prevalent.

Did composers write music about Pan because they agreed with the ideals expressed in his stories, or because Pan was having a moment and they saw an opportunity to make money? In many cases, we’ll probably never know. But even if the underlying values in Pan’s myths did not reflect the personal views of the composers themselves, these artists did create compositions that reflect anti-feminist sentiments (at least, from a 21st century point of view). And the perpetuation of those ideas continues to be a problem even today – those stories did not exist in a vacuum, and did not start or end with Romantic era composers.

The Ethics of Authenticity

This is where things get to a sticking point – there’s a tendency to be loyal to the score and/or what we perceive as the composer’s original intent, which can result in resistance to modifying pieces and/or performances. But the idea of authenticity itself is a construct, as in reality, we are often faced with practical restrictions (along with limitations in knowledge and differences in technology) that mean it’s pretty much impossible to perform pre-twentieth-century works the way they were initially staged at their premiers.

Our audiences won’t always know when we’re being loyal to the composer’s intent – but they will notice when themes revolve around problematic relationships and harmful power dynamics that contradict common values in our modern society. And when there are potential ripple effects on the perceptions of meaning conveyed to our students and audience members, it’s important to be mindful that our programming can have real impacts on the feelings of safety and support experienced by members of our musical community.

Individual Limitations

It’s also important to be mindful that when we’re dealing with issues of canonicity, we’re also confronting systemic norms – so no one person is responsible for (or capable of) solving the entire problem. Often, it comes down to creating safe spaces for honest discussion and following your individual discretion about navigating your boundaries in any given situation. And sometimes, your choices are limited.

Many years ago, I played Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune with my college orchestra. It was a well-intentioned choice by my director as a way to give me a bit of a solo feature in a gesture of support after one of my worst competition experiences ever (due to factors that were outside of my control). I deeply appreciated his confidence in me, and I truly do think that this composition is beautifully orchestrated. As I said at the top, Debussy is, aesthetically, one of my favorite composers.

This was also a piece my director had been hoping to program for a long time, and was waiting for the right personnel for a successful performance. He’d also been receiving a lot of pressure from higher-ups in the department to program music of that level. So the final decision to program l’apres-midi was ultimately out of my hands, and I did have reasons for being on board with that particular performance. However, that was a one-time deal, and I can and do choose not to play Debussy’s Syrinx on my own time.

Moving Beyond Pan

As a performer, a good practice I always go by is to research the backstories of pieces I’m considering at the beginning of the concert-planning process. I try to get my information from a wide variety of sources and disciplines wherever possible. And most importantly, I include research on the socio-demographics of audiences the music was originally intended for, in addition to details about the compositions and composers themselves.

For students, I propose teaching the broader category of Romantic era repertoire with pastoral themes as an alternative to works that center Pan himself (Pan was a nature god, so these pieces are thematically connected and many feature a similar compositional style).

This category includes 19th century works that center our connections with nature, often depicting scenes of rural life. Their subjects can include scenes of shepherds in the fields, celebrations of harvest festivals, settings of folk tunes, and popular rural dances. And although pastoral solos may incorporate myths of other Greek gods, this flexibility allows students a wider selection of content to accommodate their individual interests.

For more info about pastoral repertoire and a couple examples of modern pieces that reframe narratives about Pan, check out the links below!

(P.S. – Links in this post are not sponsored or affiliated. As usual, they’re for content from other musicians that I’ve enjoyed and/or found interesting, and I wanted to help spread the word. 🙂)

Additional Resources

Pastoral Flute Solos

Pieces with pastoral themes don’t literally need to have the word “pastoral” in their titles. Most of the ones below do – but these are just a few suggestions to help get you started. 🙂

- Claude Arrieu – Chanson de la Pastoure

- Béla Bartók – Suite Paysanne Hongroise

- Cécile Chaminade – Pastorale Enfantine, Op. 12 (originally for solo piano)

- Cécile Chaminade – Villanelle (originally for voice and piano)

- Franz Doppler – Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise

- Benjamin Goddard – Légende Pastorale, Op. 138

- Felix Mendelssohn – The Shepherd’s Song

- Paul Taffanel – Andante Pastoral et Scherzettino

- Germaine Tailleferre – Pastorale

The Real MVP of Pastoral Flute Music

There’s more to pastoral flute music than just Pan (even though he tends to steal all the attention).

Explore the ancient socio-economic history of flute music inspired by shepherds, sheep, and spending your days in the fields!

Pan: Modern Interpretations

Timothy Hagen – La brute, c’est Pan

This flute quartet reframes the myth of Pan & Syrinx from Syrinx’s point of view. This is currently one of my favorite pieces – I love how it still captures the etherealness of the forest, but with an air of mystery and foreboding. There are some really cool textures and harmonies throughout the piece, and also quotations from Debussy’s Syrinx and Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. La brute, c’est Pan is the first piece in the video, and you can find the link to purchase sheet music in the title above.

Gene Pritsker – Pan(ic) for solo flute

This unaccompanied flute solo depicts the alarm that the Greek god of nature caused in people from his mythological stories, and the resulting panic inspired by his name.

19th Century Perspectives

What’s the Deal With Victorian Music Halls?

Myths about Pan were not the only things used to warn Victorian women off of playing the flute. To learn more about the socio-historical challenges these virtuoso soloists faced (and how they got around them), check out this blog post!

Repertoire Featuring Pan

If you’re not feeling great about Pan, here are some Romantic era works in the flute canon that you might want to avoid or reconsider:

- Claude Debussy – Syrinx

- Claude Debussy – Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

- Johannes Donjon – Pan, Pastorale

- Jules Mouquet – La flûte de Pan

- Maurice Ravel – Daphnis et Chloe