I recently finished my annual update of Virtuosa Flute Solos, and also finally read the last chapter of Marcia Citron’s Gender and the Musical Canon – which has led me to a lot of reflection lately on the way I’ve set up & organized my database of flute solos by women composers.

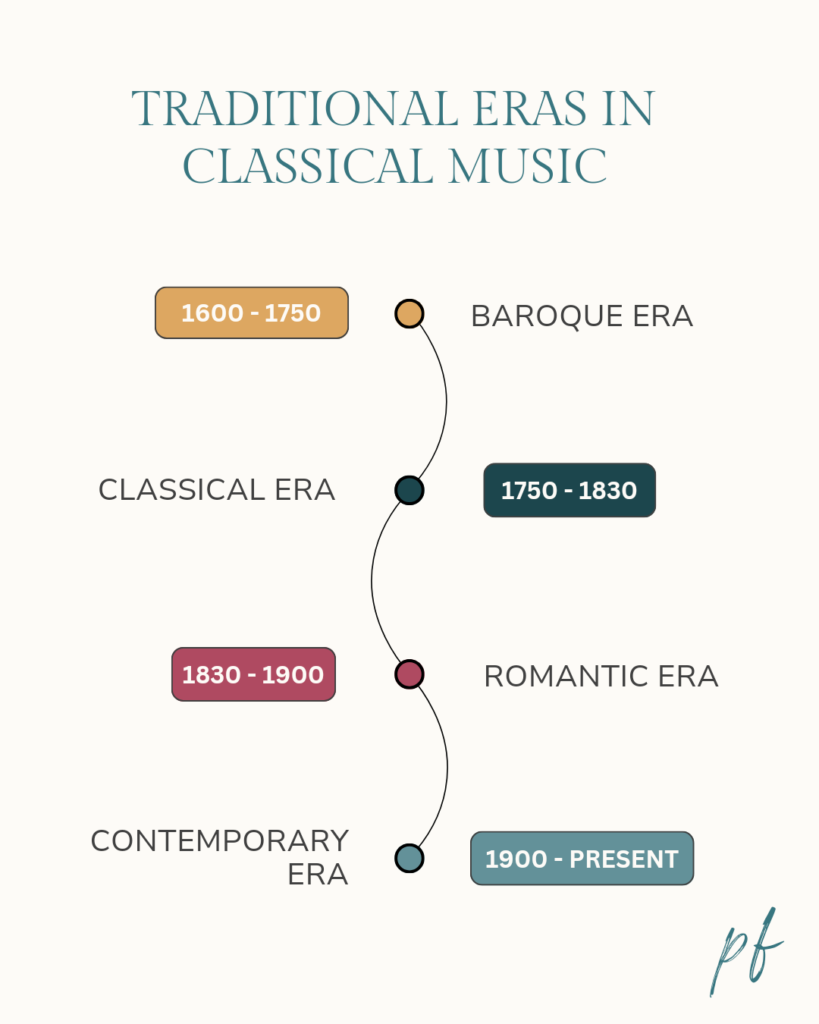

The traditional way that classical music is categorized – in Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and Contemporary eras – doesn’t always work as well as you might think when you add music by women composers to the mix.

Although “women’s music” is not a separate genre, many underlying assumptions about characteristics of these eras don’t always fit the way historical women engaged with classical music. This could range from stylistic choices, like treatment of dominant “masculine” themes versus passive “feminine” themes in sonatas, to the “bigger is better” mentality from the 1800s that promoted larger forms and ensembles, while most women wrote and performed chamber music in smaller salons.

So why do I organize my database in those eras? For the simple, practical reason that in order to be found on Google, the keywords on my webpage need to match the most common search terms. Most flutists looking for intermediate and advanced level repertoire have probably learned traditional music history from a private teacher or a standardized class in high school or college, and are used to thinking in those terms. If my goal is to make the information I’ve collected accessible to as many flutists as possible, my database also needs to be easily found.

However, my blog posts are often a place for me to think out loud, sort through, and process the things that I’ve learned about historical women musicians. And the farther I get, the more I want to tweak the timeline. There are a few spots where trends I’ve noticed among women musicians fall a few decades off from the standard eras – but I’m not sure how approach making adjustments without creating additional complications or confusion.

Although I have a performance degree, I’m also an anthropologist – so the way I approach music history also takes into account the socioeconomic context of women from each period. As a result, I tend to group women by the types of resources and opportunities for education and employment that they could access. Those also had a ripple effect in what women, as performers and as composers, were able to achieve – including the types of music that were socially acceptable for them to engage with, and what restrictions they had to find ways around.

Here’s a brief outline of my thoughts so far on what a women-centric periodization of classical music (with an emphasis on instrumental music) might look like:

1685 – 1795

I don’t know a ton about the economy of 17th and 18th century Europe, so I tend to group everything from the Enlightenment up until the French Revolution into a general category of “pre-capitalism.” Also, I haven’t done much in-depth research on music from earlier than the 1690s, so for me, the beginning of the Enlightenment makes a convenient endpoint.

In this era, musical skills were commonly learned through an apprenticeship, like learning a trade. I’ve come across several sources suggesting that this included women as well as men – and that there weren’t as many restrictions on women musicians compared to the 1800s. We tend to see women in family bands, convents, and salons of the nobility (as both patrons and as amateur musicians). However, most surviving music comes from noble courts or the church, since preserved records created from high-quality materials were expensive during this time.

1795 -1870

This era begins with the establishment of the Paris Conservatory during the French Revolution. This was the first time that music was taught in a centralized educational institution, and also the introduction of gender-segregated classes in musical instruction.

Excluded from mainstream musical societies and venues, women tended to perform in salon concerts. As a result, women composers primarily wrote short piano solos and chamber music – and by the 1830s, “salon music” had evolved its own publishing category.

It’s also important to note the technological advances of this era – pianos became more accessible to the growing middle class, and improvements in the printing press made sheet music cheaper to produce. This brought in a lot of new consumers – especially amateur musicians, many of whom were women who helped fuel the popularity of salon music.

1870 -1945

Sometime around 1870, upper-class Victorian women decided that the piano had become too popular. They wanted a different instrument to distinguish themselves, so they chose the violin and made that the cool new thing for stylish, respectable ladies. As a result, we start to see more women becoming interested in playing orchestral music and composing for a wider range of orchestral instruments – including woodwinds and brass.

Since women still weren’t allowed in major orchestras, they formed their own all-women ensembles – the most famous of which being the Neue Wiener Damenorchester and the Erstes Europäisches Damenorchester, both founded and conducted by Josephine Amann-Weinlich. The former was a chamber orchestra that went on extensive tours in Europe and the U.S. – it was the first big (in terms of fame & popularity) women’s orchestra, and inspired many women to form chamber orchestras and music clubs in the countries they toured. The latter was the first all-women symphony orchestra evidenced in surviving records.

This time period overlapped with the suffrage movement and first wave feminism. It also includes the World Wars – when women entered the workplace in many industries to help fill the absences created when men were drafted. There was a lot of activism by women’s musical organizations as a result – and although they were not allowed to keep the orchestral chairs they won after WWI, they finally became more accepted in major ensembles following WWII.

As far as the music itself, this is a transitional late-Romantic/early 20th century period where we see many women cracking the glass ceiling – Cécile Chaminade was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, Lili Boulanger won the Prix de Rome, Katharine Eggar founded the Society of Women Musicians, and Ethel Smyth published her first writings on feminist musicology.

1945 – Present

I considered splitting this period up, since it encompasses a lot of musical trends – but I feel like we’re still kinda stuck in terms of progress in women’s representation. Almost all women’s clubs disbanded as their musicians moved into the newly co-ed major orchestras, and the need for outside educational opportunities and peer support groups diminished as women were allowed to earn degrees from universities and conservatories.

“I think of all the years I spent thinking, writing, speaking, organizing, performing; and yet, your generation is just starting to ask the same questions to which we thought we had all the answers.”

Frédérique Petrides

However, when women entered those spaces, the history of the struggles and achievements of women musicians from the previous era was not incorporated into the educational curricula – and as a result, we’ve lost a lot of traditions and knowledge that came about from those women’s experiences.

This period includes 2nd wave feminism – and the 1990s saw the publication of a few influential books in feminist and queer musicology and academic conferences highlighting studies of women musicians and composers. However, that resurgence in interest is only a start – or maybe a next step. In order to actually move on, we’re gonna need to start teaching this side of music history and thinking more outside the box.

Periodization… more like guidelines, anyways?

I’m not sure what I would actually name these periods… which is another reason I’ve been hesitant to rearrange my blog post tags. Additionally, some traditional categories do line up with trends among women composers – for example, 1830 is generally considered the beginning of the Romantic era, and it’s also the decade when salon music became a big thing.

I guess that’s all to say, there’s no one right or wrong way to categorize your music – it just depends on your priorities, and the information you want to emphasize. And while periodization, as a framework, can provide a useful tool for learning, it’s also important to remember that history deals with real human beings – who are multifaceted and rarely fit neatly into categories.

So maybe the more important thing is to be open to flexible thinking, instead of blindly accepting that popular historical narratives are simply “just the way things were.” Because I honestly doubt that any single all-encompassing method of classification that works for everyone is even possible – but maybe that’s not such a bad thing after all.

Additional Resources

3 Books on my TBR List for Gender Studies & Classical Music

Want to learn more about the intersection of gender studies and musicology? Check out this post for 3 suggestions on recommended reading!

Virtuosa Flute Solos Database

Explore the world of flute music by women composers with my database of 250 flute solos! This list includes music from both historical and modern times, so whether you’re looking for an alternative to C.P.E. Bach or are curious about extended techniques, I’ve got you covered!

Historical Women Flutists – from Astley to Taillart

Just because women instrumentalists aren’t commonly discussed in music history classes doesn’t mean they never existed. Read this post to meet 24 trailblazing women flutists, from ancient Greece to 20th century America!